Posted in Culture

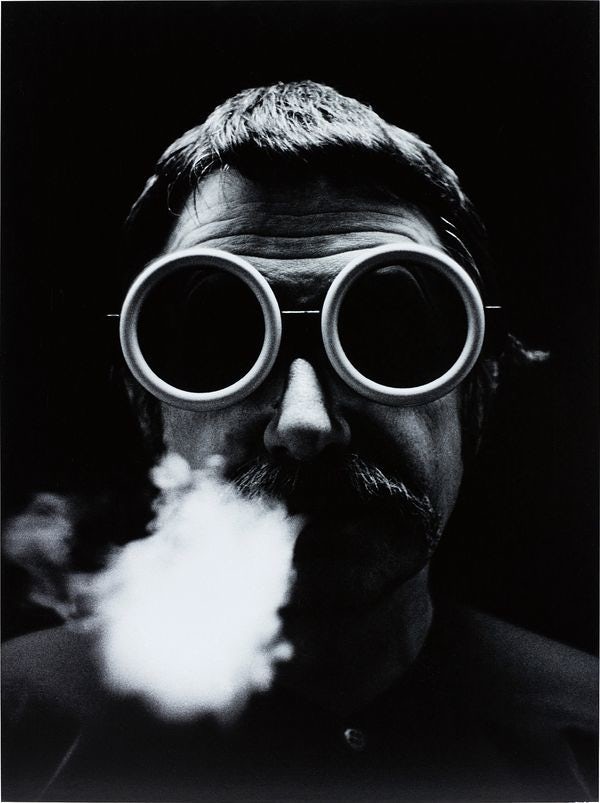

Ettore Sottsass: Breaking the Rules

It might be an understatement to call Ettore Sottsass a visionary. Every visionary must break the rules first, and he was very good at doing that. His pursuit of creating something visually stimulating through design is the legacy he left behind. Ettore Sottsass was born in Innsbruck in 1917. In 1939 he graduated in architecture at the Politecnico di Torino. Honored with numerous international awards, was the winner of the Golden Compass in 1959.

Ettore Sottsass devoted his life and work to dismantling the past in his various roles as artist, architect, industrial designer, glass maker, publisher, theoretician and ceramicist. The past to him was the rationalist doctrine of his father, Ettore Sottsass Sr., a prominent Italian architect. Fond though he was of his parents, Ettore Jr. favored a different approach. “When I was young, all we ever heard about was functionalism, functionalism, functionalism,” he once said. “[Functionalism] It’s not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting.”

In 1956, Sottsass traveled to New York as he was commissioned to create a line of ceramics during this visit, but was also inspired to concentrate on industrial design, rather than architecture, after spending a month working in the studio of the US designer, George Nelson.

You have to think of Memphis as sort of a punk movement against modernism

By the late 1970s, Sottsass was working with Studio Alchymia, a group of avant-garde furniture designers including Alessandro Mendini and Andrea Branzi, on an exhibition at the 1978 Milan Furniture Fair. Two years later, Sottsass, then in his 60s, split with Mendini to form a new collective, Memphis, with Branzi and other collaborators who were in their 20’s, including Peter Shire, Michele De Lucchi, George Sowden, Matteo Thun and Nathalie du Pastier. Sottsass was considered the key source of inspiration and the binding force within Memphis. Ettore Sottsass sent shockwaves through the design world when he unveiled the first collection from the Memphis Group. Exploding with a riot of off-kilter forms, bright colors, and outrageous patterns, the group’s cabinets, bookcases, tables, and lamps (which used plenty of plastic laminate) and broke all the rules of subdued modern design.

Memphis embodied the themes with which Sottsass had been experimenting with his mid-1960s ‘superboxes’: bright colors, kitsch suburban motifs and cheap materials like plastic laminates. This time, however, these thematics captured the attention of the mass media as well as the design cognoscenti, and Memphis (named after a Bob Dylan song) was billed as the future of design. For the young designers of the era, Memphis was an intellectual express lane, which liberated them from the dry rationalism they had been taught at the college and enabled them to adopt a more fluid, conceptual approach to design. Despite the fact that Memphis collective’s work was exhibited all over the world, Sottsass quit in early 1985.

Revered internationally as a key figure of late 20th-century design, Ettore Sottsass is cited as a role model by young foreign designers, such as Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, for the breadth as well as the quality of his work. As further testimony to his impact, in 1999 Sottsass received the Sir Misha Black medal for his outstanding contribution to the field of design. In the 2000s his work was the focus of some exhibitions and retrospectives. For example: the 2006 exhibition ‘Ettore Sottsass’ organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which was the first major retrospective of Sottsass’ work in the USA, and the ‘Ettore Sottsass – Work in Progress’ exhibition displayed at the Design Museum in 2007.

If you haven’t seen this one, it’s a must. He designed the first portable typewriter ( soon to become a laptop) called the “Valentine” by Olivetti, which is parked at Moma.

He died in 2007 at the age of 90 years on the last day of 2007. He leaves behind a rich body of work that only paved the way for others.