Posted in Design Stories

Barber & Osgerby

A partnership of curiosity

On the tenth of May 2012, signalling the approaching Summer Olympics in London, the Olympic torch was lit at the Temple of Hera, Olympic. From there the torch was carried by over 8,000 people as it traversed first Greece and then the United Kingdom and her crown dependencies, in a relay culminating in its arrival at Olympic Park on July 27th. That torch, with its slender triangulated cross section and perforated golden aluminium alloy skin, brought London designers Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby into the public imagination in full light.

You can begin to read their oeuvre as a kind of proof that design doesn’t need to be directed, or to follow a specific process, or to result in rigorous outcomes. For Barber and Osgerby, the rigour comes from curiosity, from re-examining each step, drawing or object, and from new combinations, orientations or material explorations. Design, then, becomes a process of discovering rather than knowing: of finding out rather than telling. Through embracing this state of unknowing, the uncertainty of their process, Barber and Osgerby seem to have formulated a productive way of first getting lost, and then coming out of that state together.

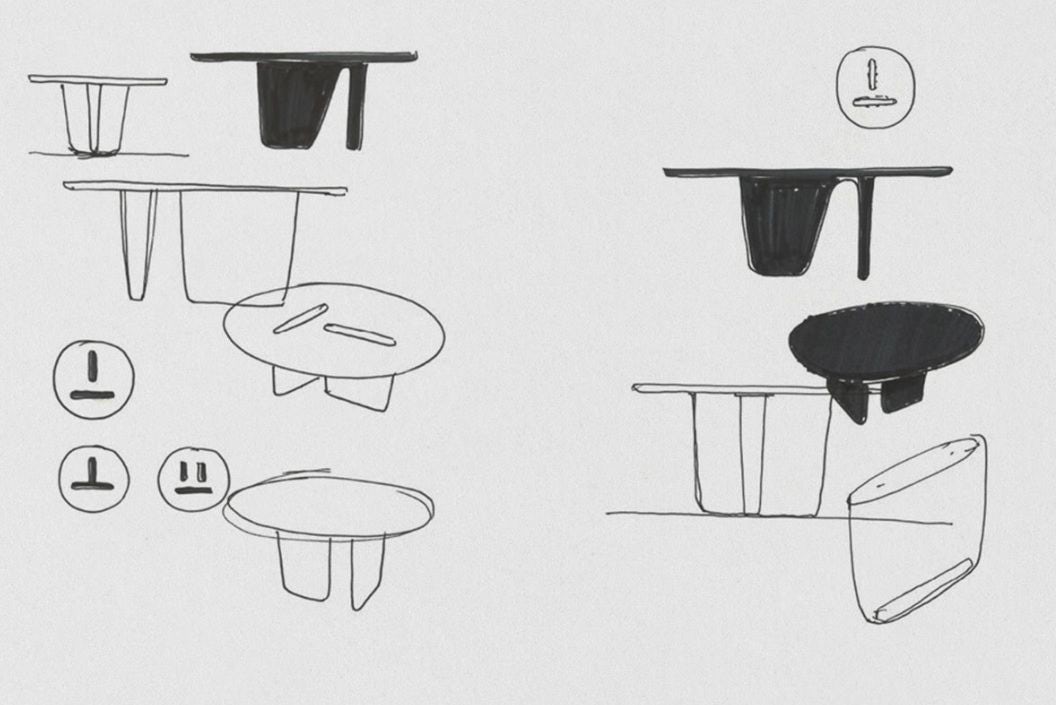

There is an intensity that breeds from this type of design process. Or, perhaps, a design process that relies on discovery and uncertainty depends on a certain intensity to drive it along. Momentum becomes key, and the best projects almost begin to feel like they drive themselves. This approach also relies on a certain level of confidence — a confidence that is built from friendship, trust, and a shared vision, and from a shared attitude to adventure and risk-taking. Fittingly then, their process remains largely analogue, with design developments happening in real-time through drawings and modeling, misinterpreted sketches and half-ideas. In their naturally collaborative process mistakes are welcomed and reinterpreted, sketches are turned upside down, models cut in half and recombined. Ideas might happen abruptly, or slowly, as if they have been lying latent within the project content until they are uncovered.

Even such an open process needs a starting point, a base for further exploration. Barber and Osgerby are tireless documentors, beginning each new design project from describing what is already known. They critically observe and draw the existing conditions, forms, uses and material relationships. The very first piece B&O designed together, as students, evolved from a simple handmade model of folded and slotted cardboard. The resulting furniture piece was configured from plywood bent into a seamless loop, becoming known as the Loop Table. Cantilevering out over the simple legs, the table has a sense of weightlessness and movement that captures the essence of that original rough card model.

The result of applying these methods over time is a broad collection of objects of a wide range of scales, functions and appearances: understated objects, where the superfluous is noticeably absent, but each with a unique personality. The Bellhop lamp, for example, arose from the idea of a candle lamp, using contemporary means to recall the traditional qualities of light and atmosphere. An exercise in formal simplicity, the mushroom-shaped lamp reduces light to a halo around itself, creating a soft, glare-free glow in which the true light source is not visible. The bold contemporary object recalls age-old rituals as it becomes a candle, a staff to hold, a light to guide in a dark passageway in the transition from inside to outside.

The Tobi-ishi table began from a study of large ornamental stepping stones often found in japanese gardens, which represent balance and harmony. Sculptural in character, the table is formed by turning two of the pebbles on their edge, and setting them at right angles to one another to form a base support. Offset to balance the weight of the tabletop pebble balanced on top, the form of this table shifts according to the viewer’s angle of approach. Despite there being no symmetry, the table achieves a sense of balance, poise and posture. From some angles, the table appears a slender stack of rocks, and from others it is more curvaceous, rounded and sensual. Originally fabricated in an experimental hand-spread cement grout, the table has been conceived in a range of materials, continuing to test the limitations and possible transformations of the idea.

A design partnership is necessarily about two visions, how they come together, overlap, consider and reinforce one another. Developed over time, a shared confidence supports experimentation and production. For Barber and Osgerby, their partnership is the core of their work, allowing them to produce designs that move beyond their singular visions, that stretch the boundaries of what design can be, or do, or seem.