Posted in Design Stories

Fake vs Real Part I: The Capital Complex

On the surface, there is a certain absurdity in drawing a distinction between real and fake furniture. As physical items we sit and lie on, work at and eat from, our bodily relationship with furniture renders it more material, more real than almost anything else in our lives. So what do we mean by a real piece of furniture, and by contrast, what is a fake?

In the beginning, before an original piece of furniture or design object takes physical shape, there is a particular motivation; a driving force. Most designed objects are responses to the specific conditions of a place, or to the functional requirements of a particular practice. Sometimes, an idea simply grows from curiosity and joy in making.

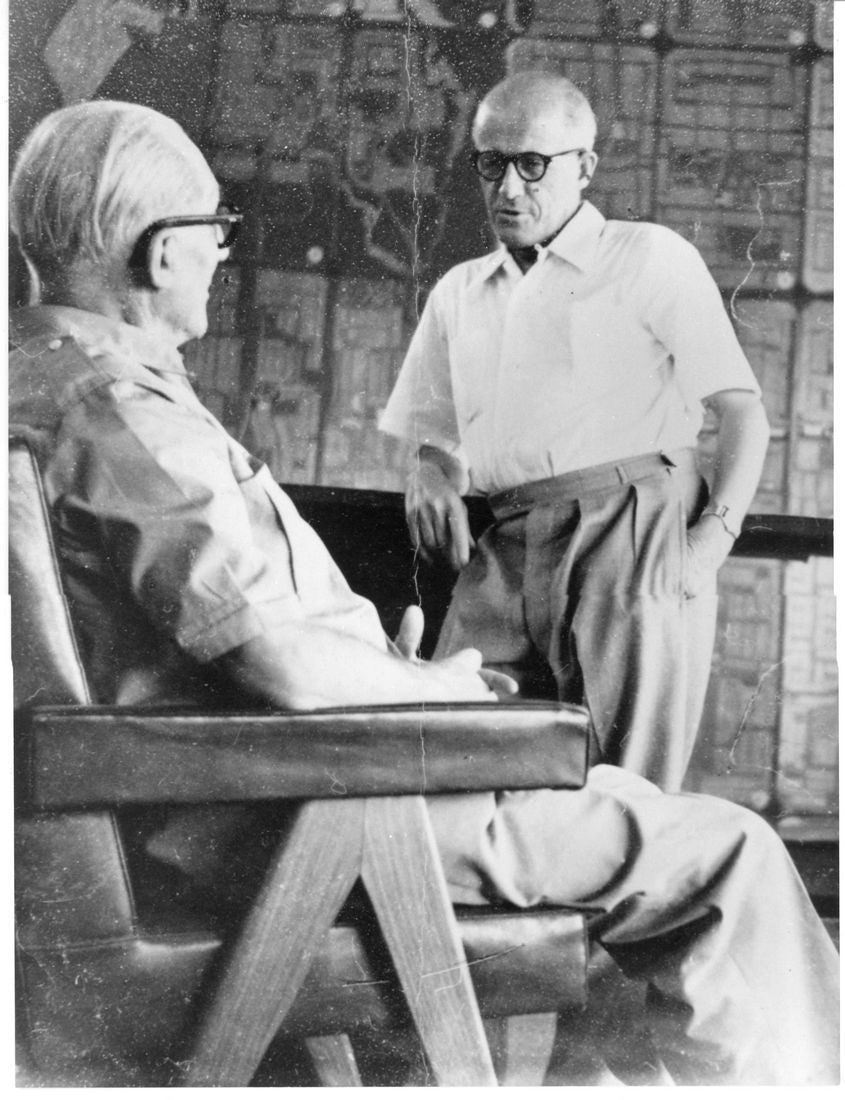

In 1951, Swiss architect Pierre Jeanneret took on the challenge of designing a furnishing collection for the project he was working on at the time with his cousin, architect Le Corbusier. Together, they were developing the architectural and urban design for the Capitol Complex in the city of Chandigarh in India. Located in the foothills of the Himalayas, the project needed furniture made en-masse that would be locally appropriate, able to be locally manufactured, and climate and bug-resistant. Responding to these requirements, Jeanneret designed a suite of sturdy teak and cane chairs, tables and benches for the formal, geometric interiors. Thousands of these furniture pieces were then hand-made by local artisans, and installed into the vast concrete chambers of the new complex.

Decades later, when parts of the Capitol Complex fell into disuse or disrepair, thousands of the chairs were left as reminders of the once lively occupation. Discarded, they landed in garbage tips, dispersed across the Indian countryside, far from those original motivations. Being alerted to what was happening from afar, international design connoisseurs made trips to locate, collect and purchase the original pieces. In testament to the durability of the design, many of the discarded chairs remained intact despite their age, requiring only minor restoration to bring them back to original condition.

Since the first exhibitions of these refurbished collections in 2009, the Capitol Complex furniture has had a second life: revered, celebrated and sought-after. The simplicity and honesty of material and form resonate with contemporary design values. And, with their distinctive presence, the hand-crafted chairs seem at home in interiors around the world. In addition to the original teak structure, license-holder Cassina has reissued the collection with new stained and natural oak finishes. Today, some seventy years on from the original inception, it is nearly impossible to browse interior magazines or social media without seeing a cluster of Pierre Jeanneret Capitol Complex chairs.

But there is an undercurrent to this story of renaissance; a dark side to the hyper-popularity of the Capitol Complex chairs. Popularity indicates widespread desire, and capitalizing on that desire is an opportunity for profit. And so, much like in the world of fast-fashion, furniture and object design is increasingly the victim of knock-offs, with a proliferation of fake designer pieces appearing on the market. Fakes are parasitic; their value depends completely on the real pieces. They live off the original design, cling to the aesthetic and brand, and ride the marketing waves.

The prevalence of fakes is a growing issue for the design industry. The replica furniture industry began in earnest in the mid-2000s, as a way to reproduce the many iconic mid-century designs that were no longer protected by the copyrights that had ceased years after their designers’ deaths. But changes in how we notice, identify with and acquire objects for our homes have extended the role that fakes play in the global design landscape. As our lives have shifted online, visual sharing platforms such as pinterest and instagram have accelerated not just the visibility, but also the desirability of specific objects and pieces. Suddenly, everything feels attainable. If a certain chair reappears frequently on social media feeds, there is a sense that everyone else owns one — and that by association, you should, and can, too. While vintage originals from the Corbusian city at the base of the Himalayas might be in limited supply, an online search yields multiple dealers offering products that appear to have the same names, shapes and specifications. Clever marketing makes the relationship of these manufacturers to the original design and licensed reproducers even murkier. The growing prevalence means many people are buying fakes without realizing it, unaware of the hidden costs and impacts.

While shopping online, in a virtual work, the physical and material qualities of a piece fall into the background. Our focus is on finding the best deal. For a real design piece, it is easy to imagine that the price tag is largely in the concept: the idea of the product, how it looks, and the famous name it carries. In reality, a large portion of the cost lies in the value of a robust, ethical development and production process. As physical objects, the structure, finishes and crafted material relationships are fundamental. Whatever the initial motivation, moving from the sketchy beginnings of an idea towards the completed piece is a process of refinement. A designer can devote years to a particular product or product line, developing their thinking from initial concept to market launch. The process is typically iterative, working with full-scale mock-ups, with each test disclosing new possibilities. Through the production process, new techniques are identified, to be further investigated in future pieces.

The integration of process with design thinking is at the core of many design companies. The innovation is not only evident in how a piece looks, but also in the physical object itself. For individual furniture pieces, intricate manufacturing techniques might be developed to enable slender supporting elements without sacrificing strength, or to give the illusion of massiveness without becoming too heavy. Quality pieces use quality materials, ensuring a piece will last for generations to come. The process also relies on paying a fair wage to each member of the production team, from those sketching initial ideas, to those prototyping, testing new material possibilities or developing the marketing material. And finally, a robust design and manufacturing process also covers safety and strength testing, something that many manufacturers of fakes do not spend time on. Choosing fake products for a bargain price ignores these aspects that a higher price accounts for.

Beyond finding a bargain price, purchasing a fake can also be driven by accessibility and availability. Original pieces are often carefully produced to order, resulting in longer lead times. In a retail landscape where we expect immediacy, real pieces demand patience. On the other hand, stores offering fakes tend to be more widely and immediately available, producing en masse in locations with cheap labor, then storing pieces prior to final shipping. This approach results in significant waste, and often relies on labor that is less-likely to be adequately reimbursed. It is often said that time, cost and quality operate in a push-pull relationship to one another, such that it is not possible to have all three at once. Producers of fake goods may be able to promise lower prices or quicker delivery times, but not without compromising the quality of what they produce, or how they produce it.

As they flood the market, more methods for developing and manufacturing fakes are being developed. With digital drawing files of originals being made available in manufacturers’ online catalogues, the increased transparency is a gift to copy artists. So although questions of ethics and design integrity are always present, other compromises can be less immediately obvious. Perhaps the most visually apparent is quality. A fake design may be overly heavy for its size, or its strength may be incorrectly distributed so that over time the rear legs of a chair warp in comparison to the front. Colors lose their luster more quickly, fabrics pill or shed, and wood may mark or split. Fake pieces frequently make use of cheaper, non-sustainably sourced materials, that are less likely to wear well, and in some cases include toxic glues or fibers. With both materials and craftsmanship lacking longevity, a replica will rarely have the lifespan of an original. Where copies focus on replicating the aesthetic image of a piece, the quality is often compromised in hidden ways.

When Pierre Jeanneret set about designing the Capitol Complex pieces, part of his focus was on designing an honest piece that would last. With the recent reincarnations, his design transcends the time-frame and use that he initially envisaged. Today, real pieces and their fakes co-exist in a complex way, with the differences often clouded or minimized. Yet the question of what constitutes a real or a fake is not purely theoretical. Each piece is evidence of a body of work, a material process, a physical construction process. And it is in this real, physical world, that we engage in with our bodies as much as with our minds, that a fake quickly reveals itself. Lacking quality, a fake is often characterized by poor craftsmanship, discomfort and limited longevity, disregarding sustainability or ethical production methods. The absurdity, then, isn’t in drawing a distinction between real and fake furniture items, but in failing to do so.