Posted in Design Stories

Jean Prouvé: Posture and Play

It’s not often you describe a chair as having posture, but that’s exactly how Jean Prouvé’s Standard Chair sits: with posture. The simple four limbs, seat, and back hold in a particular way. The arrangement is almost insect-like, with the exoskeleton of shaped rear limbs and fine steel-tube front legs exposed. The limbs, constructed from discrete parts, lean together, not lazily, but with the kind of energy that synergizes, inviting occupation. The Standard Chair calls out to be sat on, a poised, ready structure.

Designed in 1934, the precise posture of the standard chair comes from the marriage of form and function evident across Prouvé’s broad oeuvre. A self-taught designer, engineer, and architect, Prouvé was born into a workshop life. His father, Victor Prouvé, was a painter, sculptor, and designer who worked with many materials, from paint and metal to leather and jewels. A member of the Art Nouveau École de Nancy, Victor Prouvé collaborated with artists, architects, and designers, celebrating the new possibilities of industrial methods and exploring forms and aesthetics arising from them.

From photographs of the time, it’s not hard to imagine Prouvé’s childhood as a sensory adventure awash with embroidery motifs, bronze casts, and exquisite tapestries. Exposed to the intersection of art, architecture, and engineering from a young age, the workshop spirit and the mélange of influences and concerns flooded Prouvé’s burgeoning practice. He saw how materials could be used in various situations and how the world could inform design.

Throughout his life, Prouvé gave himself up studying and playing material. After three years at a school of fine arts, he spent time apprenticing as a blacksmith and in a metal workshop in Paris, developing an intimate knowledge of metal and honing his practice. Learning from these workshop scenarios, he grew his design thinking through prototyping — conceptualizing, fabricating, and learning from the fabrication. In tandem with making, Prouvé also sketched extensively, turning the design object over, taking it apart, and putting it back together in many ways on a single page. Parts or components that weren’t quite right for one project would incorporate into the next. Images would reappear in different guises, at different scales, and in other relationships.

But it was the workshop that would become an ongoing motif in Prouvé’s life. His work embodies the sense that the design was not about making for others but about making with others, the collective skills, effort, and play that would enable a certain kind of production and life. This was a very defined, studious play. Today we might call this type of work research: a particular type of research that takes place not by studying books but by studying materials, forms, and processes and paying attention to the world in which design plays out. We might even call it research by design or research by living. As a result, Prouvé’s methods are resourceful, supremely rational, and ingenious.

Amidst his social concerns and engineering background, there’s an assumption that Prouvé was not concerned with aesthetics. Nonetheless, his pieces have a specific aesthetic, which ties them together as a family across scales and lines of use. It’s the kind of aesthetic that is difficult to pre-think. Instead, it becomes honed and defined through iterative testing and learning processes. Knowledge of how a piece of metal bends can be shaped to carry a specific load or might be cut out to reduce weight and material use where it is not needed produces specific outcomes that, carried out, again and again, form a language. The Standard Chair, for example, is standardized in that it is easily fabricated, but aesthetically it departed from standard notions of normalcy.

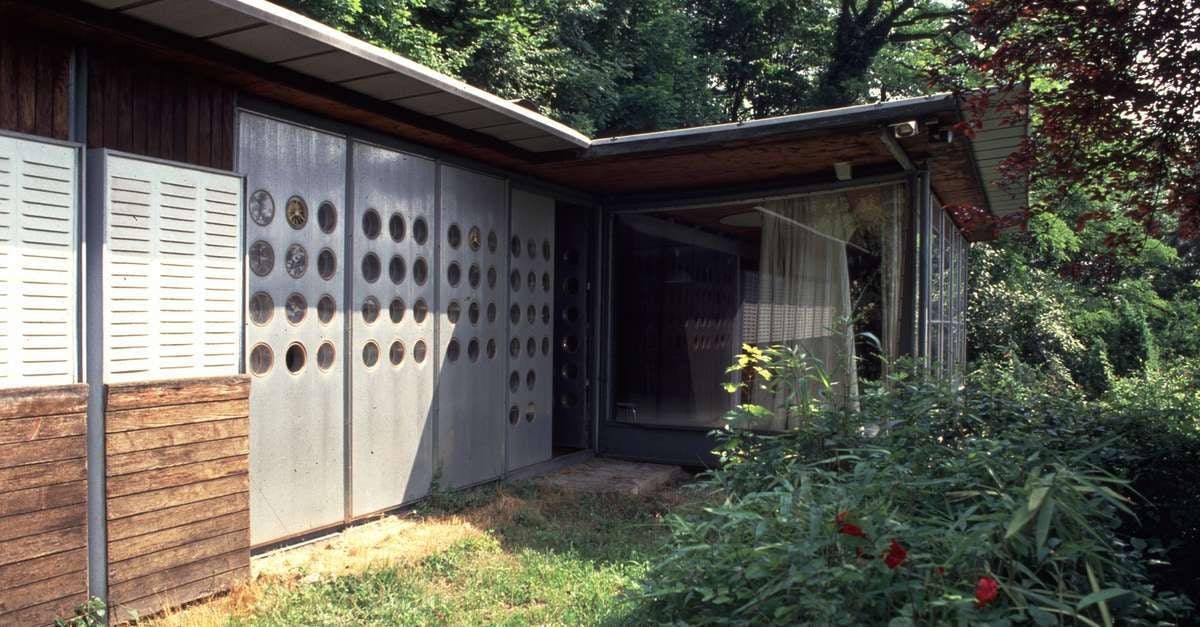

There’s evidence that Prouvé was cognisant of this language-making process. He was able to identify it and take control and play with it. In his own house, the iconic Maison Prouvé, circular cut-outs originally generated to save material became the form of windows. These windows then took on a port-hole-like narrative, turning tiny bedrooms into ship cabins and emphasizing, by contrast, the expansive glazed view from the living room.

At the scale of furniture, we find the presence of architecture: structure laid bare, the lightness of bridges, the planar roof or tabletop. The splayed table legs of the Compass Desk, originally constructed en masse for the Cité Internationale University in Paris, were scaled up to form a verandah at the Sécurité Sociale building in Le Mans, and to frame a refreshment bar in Evian. Bent plywood could operate at the scale of a seat or be combined to form a screen.

The many démountable houses Prouvé developed to be mass-produced for post-disaster or economical housing scenarios. These houses typically grew around a modular grid, with orthogonal geometries, the bent ply components he often returned to in furniture eschewed arbitrary right angles, leaving nothing square. Instead, each part was shaped not for ease of flat packing and construction but to allow the material components to be slung together most efficiently, to translate the body’s forces through the object. Turning his back on tubular steel parts, which he considered overused and inappropriate, Prouvé worked with simple sheet metal, cut and folder pressed, finished with car paint, and grafted together.

With posture comes presence, and pieces like the Compass Desk or the Standard Chair display this. Each takes on solidity in space, owning and orienting an interior. When architecture focuses on providing essentials, as the simple, mass-produced demountable houses were, this orienting relationship between architecture and furniture becomes powerful. Jean Prouvé extended opportunities of space and making to create ways of living and working together that aren’t merely resourceful but are also astoundingly humane and beautiful.